Autistic individuals may experience differences in how they engage with peer relationships at all ages.

These differences, shaped by unique communication styles, sensory preferences, and interests, can sometimes make traditional social interactions challenging, primarily due to societal expectations and misunderstandings. Autistic children and adolescents may navigate friendships in ways that are not always recognised or valued by their peers, leading to experiences of social isolation or peer bullying. These experiences can impact self-identity, self-esteem, and the transition to adulthood.

In adulthood, the landscape of social connections can continue to present challenges, with some studies indicating that a smaller proportion of Autistic adults report having friends and that they may experience higher levels of loneliness compared to non-Autistic adults. However, it’s important to recognise that Autistic individuals often express a strong interest in forming meaningful relationships, including romantic ones, even though societal barriers may make this more difficult.

Strong friendships and supportive relationships can serve as a protective factor against the negative impacts of social challenges. For many Autistic individuals, connections based on shared interests and mutual respect are key to feeling accepted and valued. Friendships and peer support not only have the potential to reduce feelings of loneliness and depression but also to promote peer acceptance and enhance self-worth. Supporting Autistic people in developing and maintaining social relationships of their choosing – whether with peers, friends or partners – is crucial for their overall quality of life, while also respecting those who may prefer less social engagement. This support should honour their individual preferences and respect their autonomy, recognising that the quality and nature of social connections can vary widely among Autistic individuals.

Social Skills Training

Social Skills Training (SST) is often used to help Autistic individuals develop and navigate friendships and relationships. Programs such as PEERS and the Secret Agent Society are commonly used in group settings while one-on-one approaches might include methods from resources like The Hidden Curriculum and Social Thinking.

The primary aim of SST should be to support Autistic individuals in understanding social interactions and to foster positive, meaningful connections with others, based on their own goals and preferences. Various strategies are used, such as direct teaching, role-playing, modelling and group activities. Research on SST often examines whether participants increase their social knowledge and whether their social behaviours align more closely with those of non-Autistic people. However, it’s crucial that SST focuses on enhancing well-being, confidence, and authentic connection, rather than merely teaching Autistic individuals to mimic neurotypical behaviour.

For instance, a study by Gates et al. (2017) found that SST can have a medium effect on improving social skills, as observed by participants themselves, their parents, teachers, and through social tasks. Other studies report similar results, with small-to-moderate improvements in social knowledge or behaviour. Additionally, some research suggests that SST may enhance well-being and quality of life, although it’s not always clear if these improvements are recognised by the participants themselves or primarily by their parents.

While SST can be effective in promoting certain social skills, there is a growing discussion, led by Autistic people, about the underlying assumptions of these programs and their real impact.

Concerns that have been raised include:

- the possibility of publication bias, where studies with negative or neutral results might not be published, leading to an incomplete picture of SST's effectiveness

- the fact that many SST programs are tested in controlled settings rather than in everyday environments, which can limit their practical application

- a focus in evaluations on changes in social knowledge or behaviour without fully considering the experiences and perspectives of Autistic participants themselves

- the lack of attention in some studies to potential negative effects of SST on participants

- the possibility that some SST programs may not reflect the latest understanding of how social interactions actually work

- concerns that SST could unintentionally increase stigma by reinforcing rigid social norms and encouraging masking (suppressing one's authentic self), which can be harmful to mental health. While it’s important not to pressure Autistic individuals to conform to neurotypical social norms, providing them with the knowledge of these norms can empower them to make informed choices about how they wish to interact.

Fundamentals of best practice – neurodiversity-affirming social supports

A neurodiversity-affirming approach to supporting social relationships means that goals, therapy approaches, and materials used should teach Autistic children and adults that their ways of communicating and socialising, while different from neurotypical people, are not wrong. Unlike many conventional SST approaches, a neurodiversity-affirming approach does not teach Autistic people that they need to “act” more like neurotypical people.

Some key principles of neurodiversity-affirming social supports are outlined below.

Individualised goal setting

The goals should be based on the person’s own social goals and/or any particular skills they want to improve. For adolescents and adults this can include "individual trouble-shooting" with a therapist i.e. assistance for the person to work out that they want from platonic/romantic relationships, what they are doing well and what they might need to work on to reach their goals.

Supporting authentic social interaction

The aim should always be to build understanding of the social world in order to meet those self-determined goals, not to “fix” or “change” someone. Some examples of social skills goals that seek to change the person’s natural behaviour and should be avoided include:

- modifying voice tone

- making eye contact

- imitating neurotypical body language

- imitating neurotypical facial expression

- learning and repeating rote scripts in social situation

- reducing/eliminating stimming behaviour

- prioritising group and imaginative play over solitary, concrete or repetitive play

- encouraging initiation of play with peers when solo time is preferred

- tolerating unwanted touch

- topic maintenance of communication partner's choosing for so many turn-takes.

Inclusive and respectful resources

Any materials or methods used should be reviewed to ensure they do not imply that Autistic traits are inherently bad. Neurotypical social mannerisms/preferences are presented in a neutral fashion and as an option to consider.

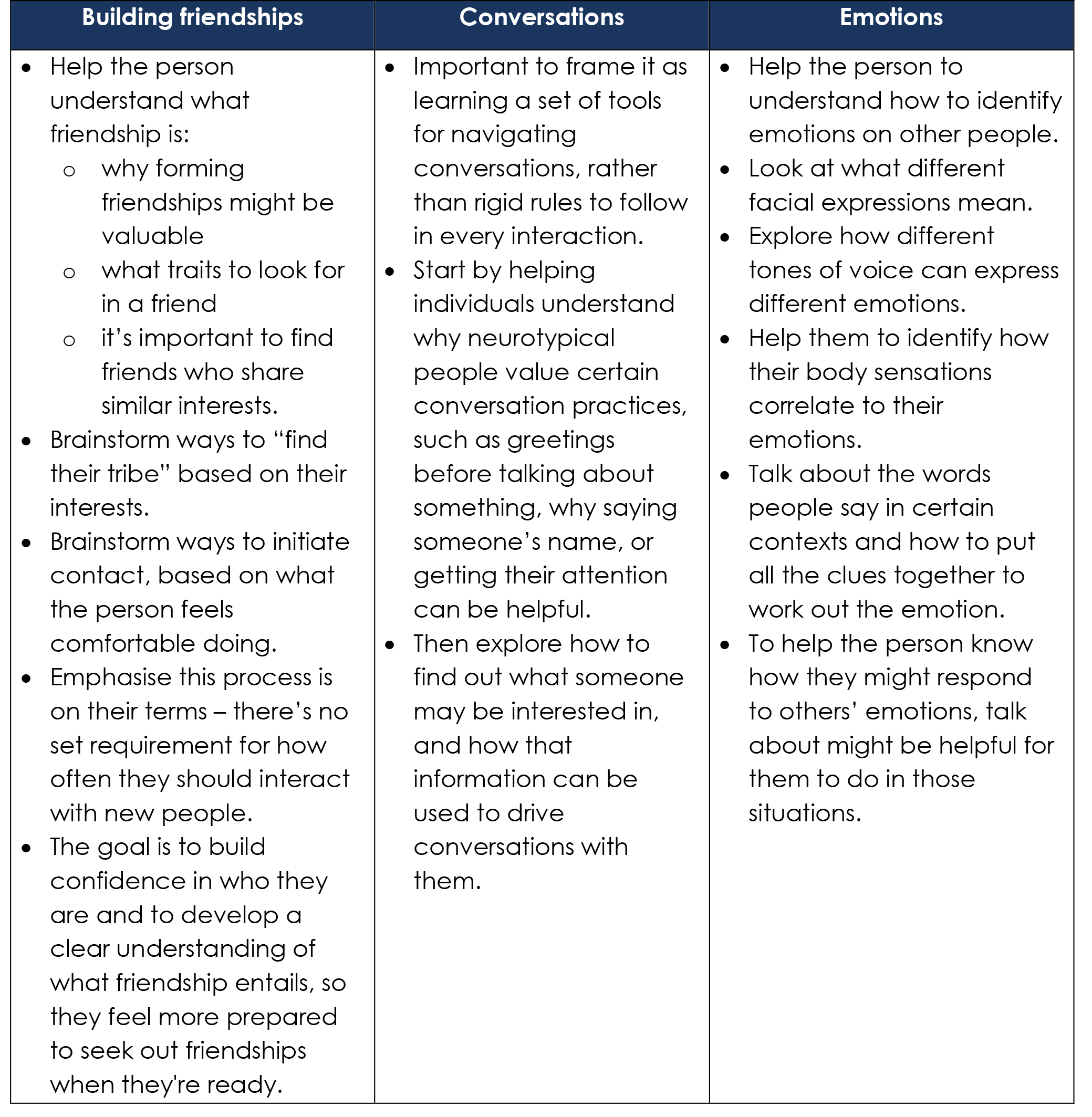

Examples of neurodiversity- affirming approaches to social supports:

Adapted from: www.twinkl.com.au/blog/author/sam-rowntree

Teach self-advocacy skills

Being able to self-advocate allows Autistic people to maintain their boundaries, reduce vulnerability and improve mental health. This involves supporting individuals in using their preferred communication methods, whether through a speech-generating device, spoken language, sign language or other systems, and educating others to accept these methods. It also includes equipping individuals with the language they need to advocate for themselves, whether it’s addressing sensory needs, explaining conversational differences or expressing other important aspects. The key to effective self-advocacy is also educating the people around the individual so that they are receptive and understanding.

Fostering mutual understanding in communication

Perhaps most importantly the onus for effective two-way communication and relating should not be solely on the Autistic person. As explained by Dr Damian Milton's double empathy problem, neurotypicals should also learn about the differences in neurotypes so that there is more understanding and acceptance in the community. When working with Autistic individuals it is important that those in their immediate social network – family, peers, support workers, employers/colleagues are provided with an understanding of Autistic ways of communicating and socialising through formal training or access to neurodiversity-affirming information and resources.

Additional resources

Ambitious about Autism – Relationships and intimacy my way: an autistic perspective